What Animal Was Used To Carry Cargo On The Silk Road

Aboriginal Roman mosaic depicting a merchant leading a camel train. Bosra, Syrian arab republic

"Caravan Budgeted a City in the Vast Desert of Sahara", from: Stanley and the White Heroes in Africa, by H. B. Scammel, 1890

Camel train transporting a house, Kalgoorlie, Western Australia, ca. 1928

Camels with a howdah, by Émile and Adolphe Rouargue, 1855

A camel railroad train or caravan is a series of camels conveying passengers and goods on a regular or semi-regular service betwixt points. Despite rarely travelling faster than man walking speed, for centuries camels' ability to withstand harsh weather condition made them platonic for advice and trade in the desert areas of North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Camel trains were also used sparingly elsewhere around the globe. Since the early 20th century they take been largely replaced by motorized vehicles or air traffic.[i]

Africa, Asia and the Middle East [edit]

By far the greatest use of camel trains occurs between Due north and West Africa by the Tuareg, Shuwa and Hassaniyya, as well as by culturally-affiliated groups like the Toubou, Hausa and Songhay. These camel trains conduct trade in and around the Sahara Desert and Sahel. Trains travel as far south equally key Nigeria and northern Cameroon in the west, and northern Kenya in the east of the continent. In artifact, the Arabian Peninsula was an important route for the merchandise with India and Abyssinia.

Camel trains accept as well long been used in portions of trans-Asian trade, including the Silk Road. As tardily every bit the early twentieth century, camel caravans played an of import role connecting the Beijing/Shanxi region of eastern China with Mongolian centers (Urga, Uliastai, Kobdo) and Xinjiang. The routes went across Inner and Outer Mongolia. According to Owen Lattimore, who spent 5 months in 1926 crossing the northern edge of China (from Hohhot to Gucheng, via Inner Mongolia) with a camel caravan, demand for caravan trade was only increased by the arrival of foreign steamships into Chinese ports and the construction of the first railways in eastern China, as they improved access to the earth market for such products of western China as wool.[2]

Australia [edit]

In the English-speaking world the term "camel train" oftentimes applies to Commonwealth of australia, notably the service that one time continued a railhead at Oodnadatta in South Australia to Alice Springs in the center of the continent. The service concluded when the train line was extended to Alice Springs in 1929; that train is called "the Ghan", a shortened version of "Afghan Limited", and its logo is camel and rider, in honor of the "Afghan cameleers" who pioneered the road.[3]

North America [edit]

- United states

The history of camel trains in the U.s.a. consists mainly of an experiment by the United States Army. On April 29, 1856, 30-3 camels and five drivers arrived at Indianola, Texas. While camels were suited to the job of transport in the American Southwest, the experiment failed. Their stubbornness and aggressiveness made them unpopular among soldiers, and they frightened horses. Many of the camels were sold to private owners, others escaped into the desert. These feral camels continued to be sighted through the early 20th century, with the last reported sighting in 1941 near Douglas, Texas.[four]

- British Columbia, Canada

Camels were used from 1862 to 1863 in British Columbia, Canada during the Cariboo Gold Rush.[v]

Camel caravan system [edit]

While organization of camel caravans varied over time and the territory traversed, Owen Lattimore's account of caravan life in northern China in the 1920s gives a good idea of what camel send is like. In his Desert Road to Turkestan he describes mostly camel caravans run by Han Chinese and Hui firms from eastern People's republic of china (Hohhot, Baotou) or Xinjiang (Qitai (so called Gucheng), Barkol), plying the routes connecting those 2 regions through the Gobi Desert past style of Inner (or, earlier Mongolia'southward independence, Outer) Mongolia. Earlier Outer Mongolia's effective independence of Mainland china (circa 1920) the aforementioned firms also ran caravans into Urga, Uliassutai, and other centers of Outer Mongolia, and to the Russian border at Kyakhta, just with the cosmos of an international edge, those routes came into turn down. Less important caravan routes served various other areas of northern Red china, such as most centers in today's Gansu, Ningxia, and northern Qinghai. Some of the oldest Hohhot-based caravan firms had a history dating to the early Qing Dynasty.[2]

Camels [edit]

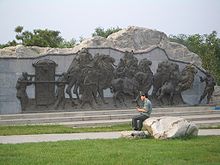

A modernistic sculptor's depiction of (the head of) a caravan approaching Beijing, complete with a camel-puller and a mounted caravan chief, head melt, or xiansheng riding next to him. In the deserts of Mongolia, one would not run into a dignitary in a sedan chair travelling along, nor would a baby camel back-trail its mother.[six] Yet, Mildred Cable and Francesca French in their book The Gobi Desert (1942) draw how a young camel can exist carried in a wooden cradle on its mother'southward back. After the showtime week information technology is capable of walking beside her with periods of rest in the cradle; as it grows older it becomes capable of carrying a load of lighter articles needed by the caravan only at four years one-time can conduct a full load.[vii]

Caravans originating from both ends of the Hohhot-Gucheng route were equanimous of two-humped Bactrian camels, suitable for the climate on the expanse, although very occasionally i could see unmarried-humped dromedaries brought to this road past Uighur ("Turki", in Lattimore'southward parlance) caravan people from Hami[8] A caravan would be usually composed of a number of files (Chinese: 连, lian), of upwards to 18 camels each. Each of the rank-and-file caravan men, known as the camel-pullers (Chinese: 拉骆驼的, la luotuo-de), was in accuse of one such file. On the march, the camel-puller's task was to lead the kickoff camel of his file by a rope tied to a peg attached to its nose, each of the other camels of the file existence led by means of similar rope by the camel in front end of information technology. Two files (lian) formed a ba, and the camel-pullers of the two files would help each other when loading cargo on the camels at the beginning of each day's march or unloading it when halted. To practise their chore properly camel-pullers had to be experts on camels: equally Lattimore comments, "because there is no good doctoring known for him [a camel] when he is sick, they must learn how to go on him well." Taking care of camels' health included the ability to find the all-time available grazing for them and keeping them away from poisonous plants; noesis of when one should not allow a camel to drinkable besides much water; how to park camels for the dark, allowing them to obtain the best possible shelter from air current-blown snow in winter; how to properly distribute the load to prevent it from pain the brute; and how to treat minor injuries of the camels, such as blisters or pack-sores.[ix]

The loading of camels was described by Mildred Cablevision and Francesca French in their book Through Jade Gate and Key Asia (1927): «In the loading of a camel its grumblings commence as the first bale is placed on its back, and continue uninterruptedly until the load is equal to its strength, but as before long every bit it shows signs of being in excess, the grumbling ceases suddenly, and then the driver says: "Plenty! put no more on this beast!"»[ten] [xi]

Azalai salt caravan expert by Tuareg traders in the Sahara desert. The French reported that the 1906 caravan numbered 20,000 camels.

Caravan people [edit]

A caravan could consist of 150 or so camels (8 or more files), with a camel-puller for each file. Besides the camel-pullers the caravan would also include a xiansheng (先生, literally, "Sir", "Mister") (typically, an older human with a long experience as a camel-puller, now playing the role of a full general manager), one or two cooks, and the caravan master, whose say-so over the caravan and its people was as accented as that of a helm on a transport. If the owner of the caravan did not travel with the caravan himself, he would send along a supercargo--the person who will have care of the disposal of the freight upon inflow, simply had no authorization during the journeying. The caravan could carry a number of paying passengers as well, who would alternate betwixt riding on summit of a camel load and walking.[2]

Camel-pullers' bacon was quite depression (effectually 2 silvery taels a month in 1926, which would non be enough even for shoes and clothing he wore out while walking with his camels), although they were likewise fed and provided with tent space at the caravan possessor's expense. Those people worked not and then much for the wages equally for the do good of carrying some cargo—half of a camel load, or a full load—of their own on the caravan's camels; when successfully sold at the destination, it would bring a handy profit. Even more importantly, if a camel-puller could afford to buy a camel or a few of his own, he was allowed to include them into his file, and to collect the carriage-money for the cargo (assigned by the caravan owner) that they would bear. One time the camel-puller got rich plenty to own close to a total file of 18 camels, he could join the caravan non as an employee but as a kind of a partner—now instead of earning wages he would be paying money (effectually 20 taels per round-trip in 1926) to the owner of (the rest of) the caravan for the benefit of joining the caravan, sharing in the food, etc.[2]

Diet [edit]

The caravan people's food was mostly based around oat and millet flour, with some fauna fat. A sheep would exist bought from the Mongols and slaughtered every now so, and tea was the usual daily drink; as fresh vegetables were scarce, scurvy was a danger.[2] Besides the paid cargo and the nutrient and gear for the men, the camels would also conduct a fair amount of forage for themselves (typically, dried peas when going west, and barley when going east, those being the cheapest types of camel feed in Hohhot and Gucheng, respectively). Information technology was estimated that, when leaving its signal of origin, for every 100 loads of trade the caravan would deport around xxx loads of provender. When that was not enough (peculiarly in winter) more fodder could be bought (very expensively) from dealers who would come to the caravan route's pop stopping places from the populated areas of Gansu or Ningxia to the south.[12]

Cargo [edit]

Typical cargo carried by the caravans were commodities such as wool, cotton fabrics, or tea, likewise as miscellaneous manufactured appurtenances for auction in Xinjiang and Mongolia. Opium was carried as well, typically by smaller, surreptitious, caravans, usually in winter (since in the hot conditions opium would be likewise easily detected past the odor). More exotic loads could include jade from Khotan,[xiii] elk antlers prized in Chinese medicine, or even dead bodies of the Shanxi caravan men and traders, who happened to die while in Xinjiang. In the latter case, the bodies had been first "temporarily" buried in Gucheng in lite-weight coffins, and when, later on 3 or so years in the grave the mankind had been by and large "consumed away", the merchant guild sent the bodies to the due east by a special caravan. Due to the special nature of the load, college freight rate was charged for such "dead passengers".[fourteen] Camels have been historically used to traffic illicit drugs among their legal trade goods. [fifteen] With camel meat being illegal in some places, Camels themselves are smuggled. In India, ritual cede and common slaughter has fueled camel smuggling.

Speed [edit]

According to Lattimore's diary, caravan travel in Inner Mongolia did non always follow a regular schedule. Caravans traveled or camped at whatsoever time of twenty-four hours or night, depending on weather, local conditions, and the need for rest. Since the caravan traveled at the walking speed of the men, the distance made in a day (a "stage") was usually between x and 25 mi (16 and 40 km), depending on road and atmospheric condition conditions, and distances between water sources. On occasions several days were spent in a camp without going forward, due to bad weather. A i-way trip from Hohhot to Gucheng (1,550 to i,650 mi or ii,490 to 2,660 km past Lattimore'southward reckoning[xvi]) could take anything from three to 8 months.[17]

Smaller caravans owned past Mongols of the Alashan (the westernmost Inner Mongolia) and manned by Han Chinese from Zhenfan, were able to brand longer marches (and, thus, embrace longer distances faster) than the typical Han Chinese or Hui caravans, because the Mongols were able to ever utilize "fresh" camels (picked from their large herd for merely a unmarried journey), every human was provided with a camel to ride, and loads were much lighter than in the "standard" caravans (rarely exceeding 270 pounds (122.5 kg). These caravans would typically travel past mean solar day, from sunrise to sunset.[xviii] Such a camel train is described in the accounts of the journey made past Peter Fleming and Ella Maillart in the Gobi Desert in the mid-1930s.

Logistics [edit]

Inns called caravanserai were spread along the route of a long caravan journey. These roadside inns specialized in catering to travelers along established trade routes, such as the Silk Road and the Majestic Route. Considering such long trade routes oft passed through inhospitable desert regions, journeys would be incommunicable to consummate successfully and profitably without caravanserai to provide necessary supplies and help to merchants and travelers.

It was necessary for camels to spend at to the lowest degree ii months between long journeys to recuperate, and the best time for that recuperation was in June–July, when camels shed their hair and the grazing is best. Therefore, the best practice was for a caravan to leave Hohhot in Baronial, only after the grazing flavor; upon reaching Gucheng, weaker camels could stay there until the adjacent summer past grazing whatever vegetation is available in winter, while the stronger ones, after a few weeks of recovery on a grain diet (grain being cheaper in Xinjiang than in eastern China), would be sent back in late winter/early spring, taking along plenty of grain for fodder, and returning to Hohhot earlier the next grazing season. Vice versa, one could leave Hohhot in the bound, spend the summer grazing season in Xinjiang, and come dorsum in the late fall of the same year. Either manner, it would be possible for the caravan people and their all-time camels to make a full round trip within a year. All the same, such perfect scheduling was not e'er possible, and it was oftentimes the case that a caravan sent out from Hohhot in Baronial would end up staying on the other end of the route until and through the next grazing season, coming back to Hohhot about a yr and a half afterward its departure. [17]

Loss of camels; camel hair trade [edit]

On almost every journey quite a few camels in each caravan would be lost. On a peculiarly exhausting section of the trip, an brute already worn out by many weeks of walking, or accidentally poisoned by eating a poisonous establish, would kneel downwards and not rise anymore. Since killing a camel was considered bad karma by the caravan people, the hopeless animal—whose death, if information technology was owned past an individual camel-puller, would be a huge material loss for its possessor—was but left behind to dice, "thrown on the Gobi" as the camel men would say.[19]

Since camels moult in the summer, camel owners received additional income from collecting several pounds of hair their animals dropped during the summertime grazing (and shedding season); in northern Cathay, the camel hair trade started around the 1880s. Later, caravan men learned the art of knitting and crocheting from the defeated White Russians (in exile in Xinjiang afterwards the Russian Civil War) and the items they had made were transported to eastern Mainland china by camel caravan. Although the pilus shed past the camels or picked from them was of form considered the property of the camel owners, caravan workers were entitled to make employ of some hair for making knitwear for themselves (mostly socks) or for sale. Lattimore in 1926 observed camel-pullers "knitting on the march; if they ran out of yarn, they would reach back to the first camel of the file they were leading, pluck a scattering of hair from the cervix, and roll information technology in their palms into the first of a length of yarn; a weight was fastened to this, and given a twist to start it spinning, and the man went on feeding wool into the thread until he had spun enough yarn to continue his knitting".[xx]

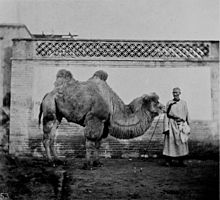

"The Pekingese Camel"; photograph past John Thomson[21]

Cultural associations [edit]

"In the Desert" ("Верблюды", literally 'Camels') is a "traditional Russian" vocal, performed by Donald Swann. He provides an English-language translation afterwards every line. The song is extremely repetitive ("Another camel is approaching"), rendering the translation largely redundant, "a whole caravan of camels is approaching".[22]

Fritz Mühlenweg wrote a book called In geheimer Mission durch die Wüste Gobi (office i in English Big Tiger and Compass Mountain), published in 1950. It was later shortened and translated into English under the championship Big Tiger and Christian; it concerns the adventures of 2 boys who cross the Gobi Desert.

See likewise [edit]

- Caravan (travellers)

- Caravanserai

- Cariboo camels

- Twenty mule squad

References [edit]

- ^ BBC: "Dying trade of the Sahara camel train" (2006)

- ^ a b c d due east Lattimore, Owen [1928/9] The Desert Road to Turkestan. London, Methuen and Co; & various later editions. Caravan logistics and organization is discussed in Chap. Viii, "Camel-Men All"; route maps are found inside the back cover.

- ^ "The Ghan; history". Not bad Southern Track. Archived from the original on 2 February 2012. Retrieved 18 Feb 2012.

- ^ Smithsonian: "Any Happened to the Wild Camels of the Westward?"

- ^ Cabiroo.com: Camels

- ^ According to Lattimore (1928/9, p. 207), while pregnant female camels could travel as part of the caravan with a total load, any infant camel born in the desert would accept to be abandoned, since, if the camel cow were to nurse the young one, she would get too thin for work.

- ^ Cable, 1000. & French, F. (1942) The Gobi Desert. London: Hodder & Stoughton; p. 162

- ^ Lattimore (1928/9), p. 151.

- ^ Lattimore (1928/9), pp. 108-115

- ^ Cable, Grand. & French, F. (1937) Through Jade Gate and Central Asia; 6th ed. London: Hodder & Stoughton; p. 21

- ^ Cable, M. & French, F. (1942) The Gobi Desert. London: Hodder & Stoughton; pp. 161-64

- ^ Lattimore (1928/9), p. 74

- ^ Lattimore (1928/9), pp. 156-157.

- ^ Lattimore (1928/ix), pp. 230-231

- ^ Irwin (2010), Camel. Reaction Books, London. p. 57.

- ^ Lattimore (1928/9), p. 100

- ^ a b Lattimore (1928-29), pp. 50-51.

- ^ Lattimore (1928/9), p. 168.

- ^ Lattimore (1928/9), p. 104.

- ^ Lattimore (1928/nine), p. 52.

- ^ John Thomson: "At certain seasons of the year, camels may be encountered in tens of thousands crossing the desert of Gobi, laden with brick tea, on their style to the Russian frontier. This brick tea, in the absence of metallic currency, forms the circulating medium in Mongolia, Siberia, and Thibet. When in the province of Peichihli I witnessed the departure of a train of two,000 of these camels laden with brick tea to exist sold in the Russian markets. These beasts are also employed in transporting coal, and other bolt, from 1 part of the province to another, and they are highly esteemed by the Mongols, as they can be hands managed, and tin can accomplish long journeys in barren regions with scant supplies of nutrient and h2o. Every bit many of my readers are aware, the camel is physically adapted for traversing the sandy plains of Asia, where they are found in the greatest numbers. The stomach is supplied with bladders which enable the animate being to carry a store of fresh water, and in like manner the humps are furnished with a store of nutrient in the shape of fatty affair which may be absorbed in instance of need."

- ^ Flanders and Swann, "At the Drop of Another Lid" (1964)

Further reading [edit]

- Fleming, Peter (1936) News from Tartary: a journeying from Peking to Kashmir. London: Jonathan Greatcoat (Peter Fleming'due south account of his 1935 bid to travel the ancient trade road from Prc to India known as the 'Silk Road'.)

- Lattimore, Owen (1928) The Desert Road to Turkestan. London: Methuen & Co.

- Lattimore, Owen (1929) The Desert Road to Turkestan. Boston : Little, Dark-brown, and Company

- Maillart, Ella (1936) Oasis interdites: de Pékin au Cachemire. Paris: Grasset

- Maillart, Ella (1937) Forbidden Journey: from Peking to Kashmir. London: Heinemann (trans. of Oasis interdites)

- Maillart, Ella (1942) Cruises & Caravans. London: Dent

- Michaud, Roland & Sabrina (1978) Caravans to Tartary. London: Thames and Hudson ISBN 0-500-27359-6 (translated from the French "Caravanes de Tartarie", du Chêne, 1977)

- Tolstoy, Alexandra (2003) The Terminal Secrets of the Silk Road: Four Girls Follow Marco Polo Across 5,000 Miles. London: Profile Books ISBN 978-ane-86197-379-five

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camel_train

Posted by: thompsonmorpegir.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Animal Was Used To Carry Cargo On The Silk Road"

Post a Comment